Memorializing as Fallism’s Feminist Alternative

Leila Easa and Jennifer Stager presented a paper about their project exploring feminist methods of memorialization at the WESWWHN Annual Conference on Gender and Commemoration in October 2021.

Fallism: toppling

monuments that symbolize patriarchal power and often white supremacy.

We

– two interdisciplinary collaborators from History of Art and English – would

like to share a bit about a project that we’ve developed over the past two

years, building on decades of collaborative work, and researched and produced

in pandemic time. We presented this project, which explores practices of

mourning, memorializing, and monumentalizing the dead, at the West of England

and South Wales Women’s History Network 28th Annual Conference in Fall 2021,

and this research has developed into an essay appearing in RES: Anthropology

and Aesthetics 75/76 (2021) and the final chapter of our forthcoming book of

essays in feminist criticism and classical receptions, Public Feminism in

Times of Crisis: From Sappho’s Fragments to Global Hashtags.

In the widest sense, our project considers the possibilities of a less patriarchal tradition of memorialization – the feminist list. While the past few years have brought deep international engagement with the idea and practice of fallism (a term that refers to toppling monuments that symbolize patriarchal power and often white supremacy), we identify and narrate a parallel heritage to that of the traditional masculine figural monument critiqued by such practices. We understand this list-based tradition to represent a feminist approach to mourning and memorializing, especially in its focus on individuals over the emblematic. We suggest that this parallel feminist tradition, stretching from ancient Greece to contemporary times, can help us contextualize both the history of such memorialization and its current practice.

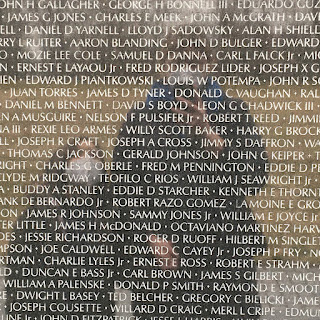

Maya

Ying Lin with Cooper-Lecky Partnership, section of the Vietnam Veterans

Memorial. Black granite, 3.23 x 150.4 m. Photo: author.

In list-based

memorials, we also see powerful possibilities for protest and activism. Such

lists engage and include a more diverse set of voices when compared to figural,

emblematic, and often patriarchal practices, yet they are equally grounded in

historical precedent. Building on Athena Kirk’s theory of apodeixis, a practice

of making a list visual, our work links together alternative monuments including

the ancient Greek casualty lists set up in Athens in the fifth century BCE, Maya

Lin’s 1982 Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, the New York Times 2020

Covid memorial cover, and contemporary feminist poetry, protest, and

performance, including #SayHerName. We argue that this tradition’s powerful

emphasis on naming and the poetic power of the list elevates not a singular

hegemony but instead a plurality of raised voices, and we suggest that its influence

is ongoing.

In the broader tradition of this alternative lineage, we also theorize the notion of reworking and repurposing as feminist and anti-racist practice. This notion can be traced through actions like the transformation of an empty plinth through site-specific work into an altar – for example, at the Harriet Tubman Grove in Baltimore, where altars honor the lives of Black women murdered by police violence by juxtaposing their framed portraits with candles, books, shells, and plants in contrast to the (now absent) equestrian monument that had formerly occupied the same space. It can also be found in the repurposing of materials for different use, as in the recent announcement that the confederate equestrian monument to Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia, around which a neo-Nazi rally took place in 2017, will be melted down by a Black-led nonprofit for a public arts project (a practice that echoes the historical melting down and repurposing of ancient bronze statues put to new purposes).

Finally, it resonates with countermonuments like Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War – a bronze sculpture that appropriates the pose and material of the equestrian portrait of Confederate general J E B Stuart but presents an unnamed young Black man seated astride a horse in an implicit protest of the genre it employs – or the work of artists whose spray-can art and light projections on a Confederate statue revise and reclaim the meaning of such work while the statue still stands. Our project, inspired by this lineage of reworking, seeks itself to rewrite the historical lineage of monumental practice, revealing overlooked narratives of feminist lists and elevating the important work of revision that continues today.

Leila Easa teaches and researches in the areas of composition, literature, creative writing, and Women’s and Gender Studies in the English department at City College of San Francisco. Jennifer Stager teaches and researches the art and architecture of the ancient Mediterranean and its afterlives in the Department of History of Art at Johns Hopkins University. Their co-written book, Public Feminism in Times of Crisis, is expected in 2022 from Lexington Books.

Comments

Post a Comment