“Would you be so kind as to let me have him back”: some thoughts on women’s work and the history of care

Kate Brooks presented a paper ‘Still seen but not heard: Bristol young people in care today, responding to the history of Muller’s Orphan Homes, Bristol’ at the WESWWHN Annual Conference on Gender and Commemoration in October 2021.

Joseph Lowe was

one of six, and nineteen months old when his parents died in 1854. Joseph Snr and

Charlotte died of cholera within a fortnight of each other, days after the

birth of Joseph’s younger sister Agnes. Willenhall, near Wolverhampton, was a

densely populated part of the industrialised Black Country, and cholera rates

were extremely high. All but the eldest (who went to work aged 11) went into

care.

I am currently

completing a doctorate on the archives of Muller’s Orphanages, in Bristol,

which contains many similar stories. Muller’s was a Victorian, evangelical

Christian institution, founded by Plymouth Brethren co-founder George Muller in

1836, and housing at any one time, around 2,000 children, including the Lowes. It

is still a religious organisation, now focused on outreach work and the Muller

museum.

Joseph Lowe, eventually orphan no.458, is my great grandfather. As a relative of an orphan, a Bristol-based foster carer, and a lecturer in Education History & Heritage, this topic drew together my interests in care history and inclusion in education, and I’ve been very privileged to be the only non-Christian to access the Muller archives, and to be able to read, talk and write about them. This research has included an art exhibition with local young people in care today.

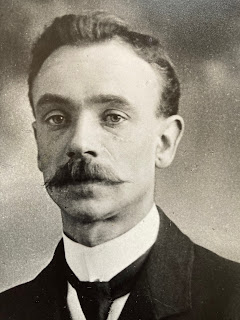

Joseph Lowe (Photo: Kate Brooks)

Initially, I had visited

Muller’s with my dad, interested in learning more about this aspect of family

history which wasn’t talked about much as he grew up. We discovered that initially

the older girls (aged 3 to 8) had gone into the workhouse, and Joseph and

Agnes, the infants, were boarded out with neighbours. A Willenhall vicar had

petitioned Muller’s to take in this ‘unusually tragic’ case, and all five were

eventually admitted by 1857.

However, Joseph’s carer, a local young woman called Lydia, had written to the institution after Muller’s had collected him and his sisters. Her letter reads desperately: she writes

“I hope you will

please to pardon the liberty I have taken but as I am so anxious for the

welfare of Joseph Lowe I shall be greatly obliged to you to let me know how he

is going on and if he makes himself contented or no”.

She continues: “I should not have parted with him but they… frightened me out of him”. She

asks if he can be returned, “Sir I have a greater favour to ask

and that is if you would be so kind as to let me have him back?”

The union officer

had added a covering note to my great grandfather’s records: Lydia had been

paid to keep Joseph and when she initially refused to hand him over, they had

stopped the payment. On the second visit, she had relented; the note implies

her resistance was about losing income, not the child.

In 2019, we had been

respite foster carers for a little girl for two years, who was taken into full

time care. This had been very difficult for us, as unfortunately issues with a

change in social workers meant we hadn’t had a chance to say a proper goodbye. I’d written to my own social worker asking to

rectify this and organise a “good” end of placement, and to “at least” be informed

as to how she was. Without realising it, I was echoing my great grandfather’s

carer, 163 years before.

It seemed to me,

researching the wider history of care for the doctorate, that whilst the care

system has obviously vastly improved in terms of understanding children’s

needs, from the Victorian era to the present day, attitudes to foster carers, is

perhaps slower in shifting. Then as now, carers – usually working class women –

are expected to “put up, mop up and shut up”, as I put it to my own social

worker. In other words, women’s work, and certainly not done for the money.

Lydia was

pressured into giving up Joseph because, of course, the middle class Victorian man,

the official, knew best. An institutional, evangelical life was preferable to

family life in the industrial slums, and in terms of training opportunities,

fresh air and job prospects, perhaps they were right. However, it was unlikely he

was reunited with siblings: girls and boys were housed separately, with very

limited contact between them. The Lowe girls were sent into service in Hackney,

Bath and Leeds, whilst Agnes was returned to family deemed “too weakly” to

work.

Foster “carers”

are significantly, not “workers” – that label reflects the valuable caring work

they do, of course, but it also implies a lower status, less professional job

than that of educators and social workers. However, this distinction is unhelpful:

foster carers work, and social workers care.

In the eighteenth

century, “respectable, trusty cottagers” would take in infants, usually elderly

women, who were caricatured by Dickens and others as baby farmers, in it for

the money. Not all of this was Victorian misogyny: Amelia Dyer from Bristol remains

Britain’s most notorious serial killer, a “baby farmer” responsible for the

deaths of over 400 infants left in her care. Reputations and stereotypes

linger, and contribute, I think, to foster caring’s continued low status,

despite the vital role carers continue to play.

I never did get a

chance to say goodbye to our foster child; it was nothing we had done, and

nothing our social worker could do. Like

Lydia, our pleas fell on seemingly deaf, official ears. I may well be a

lecturer who teaches about care and attachment to professional educators, but

the lack of response made me feel like an uppity cottager.

Our experience made

me appreciate how brave Lydia – a young working class woman – had been in

writing to the institution, challenging the decision of the middle class,

professional male, the well-regarded evangelical organisation. It made me think

about what needs to be done in acknowledging the professionalism of care and “women’s

work”. Lydia’s voice is one of the few working class female voices we hear, her

letter in the archives a rare critique of an institution, regarded in its time by

its powerful supporters (including Dickens, Spurgeon and at least three Earls)

as “a wonder even in this age of wonders”.

But now I wonder, if Joseph Lowe had had a voice at all in this, in deciding his own future, where would he have wanted to be?

Kate Brooks has been lecturing, writing and researching in Higher Education for 30 years, focusing particularly on widening participation and inclusion. She is currently teaching Education History at Bath Spa University, and leads a course for education professionals on becoming more “care aware” in schools. Kate has been researching Muller’s for the last three years, and is particularly interested in the language the institution uses to categorise the orphans’ readiness for work. A foster carer herself, she is interested in the parallels between Victorian and current day attitudes to care experienced children and young people.

Find out more about British Children’s Homes at the Children’s Homes website

Comments

Post a Comment