Dolly Pentreath: a "very singular female"

Kensa Broadhurst presented a paper ‘Dolly

Pentreath: a “very singular female’ at the WESWWHN Annual Conference on

Gender and Commemoration in October 2021. In this blog she tells Dolly’s story

and explores how she is remembered.

Dolly Pentreath’s place in history is as the so-called last

speaker of the Cornish language. As such she has a certain notoriety in both

historical and linguistic circles and is frequently mentioned in studies on

language extinction in general and the Cornish language in particular. Both her

contemporaries and nineteenth century antiquarians interested in the Cornish

language dismissed Pentreath’s claims to be a fluent speaker of the language,

and after her death she was portrayed as a figure of fun. Was this because those

commenting on her legacy were educated men who felt an uneducated woman could

have nothing of worth to contribute?

Pentreath came to public attention after Daines Barrington visited

Cornwall in 1768 to search for Cornish speakers. A guide told him he bought

fish from Pentreath who would grumble about the price in an unknown tongue. Barrington

arrived in Mousehole, where he wagered that no one could speak Cornish. Pentreath

spoke for two or three minutes in a language which sounded like Welsh. Two other

women observing this exchange laughed at her response. They told Barrington she

had been abusing him for not believing she could speak Cornish, and that they

could understand it, but not speak it.

In 1772 Barrington wrote for news of Pentreath and was told she was now eighty-seven and remembered meeting him. He received a letter written in Cornish and English by a fisherman called William Bodener who claimed that four or five other people in Mousehole could speak Cornish, one of whom must have been Pentreath.

|

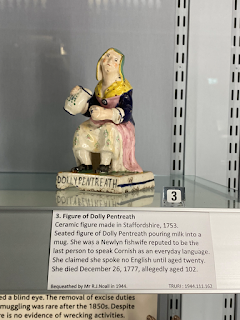

| Figure of Dolly Pentreath, TRURI: 1944.111.162, Royal Cornwall Museum, Truro (c) K Broadhurst |

Barrington’s account forms the majority of what we know

about Pentreath. The other primary sources concern her birth, the birth of her

son, a possible marriage, and her death. However, these are not without

controversy. Pentreath died in December 1777, but this has been contested, with

references to her death in 1778, likely brought about by a confusion with her

date of burial.

More obscure however, has been her date of birth. After her

death, a Thomson of Truro wrote an epitaph for her in Cornish. This epitaph gives

her age as 102 and has caused much confusion regarding what few details we can

ascertain regarding her birth. Clearer is the entry for the baptism of “John,

base son of Dorothy Pentreath,” and for Pentreath’s death: Dorothy Jeffery 27th

December 1777. A note in the register states “This is the famous Dolly

Pentreath (her maiden name) spoken of by Daines Barrington in the Archaeologia”.[1]

This implies Pentreath married; however, there are no records of the marriage

of Dorothy Pentreath and a Mr Jeffrey. Was the register trying to cover up the

fact she had a child outside marriage, despite the earlier entry making it

clear he was illegitimate? If so, who might be responsible for this? Was it her

son giving Pentreath his father’s name, or could it have been an attempt

(either contemporary or by a later hand) by the parish to sanitise the life of

their most famous inhabitant?

In 1860 a monument was erected to Pentreath by the noted

philologist Prince Louis Lucien Bonaparte. Originally it had 1778 as the date

of Pentreath’s death. In 1887, Dr Fred Jago of Plymouth published his English-Cornish

dictionary. The original manuscript, and proof editions, held at the Royal

Cornwall Museum, contain a set of letters between Jago and Mr Bernard Victor of

Mousehole which are a wealth of information on Dolly Pentreath. [2] Victor was the grandson of George Badcock,

the undertaker at Pentreath’s funeral. The letters Jago received from Victor give

more details regarding Pentreath’s position in the local area and her grave. We

hear Pentreath had a reputation for a sharp tongue, speaking Cornish, died at

the age of 102, and that Thomson’s epitaph does not appear to have been placed

on her grave. This correspondence

raised awareness of an interesting issue, the memorial stone erected by

Bonaparte was in the wrong place and brought about the removal of the monument

to the spot cited by Victor as being Pentreath’s grave. In addition the date of

Pentreath’s death was changed to 1777.

The continued interest in Dolly Pentreath can be tracked

through the British Newspaper Archive throughout the 19th and 20th

centuries encompassing local newspapers from all over Great Britain. Evidently

Pentreath’s fame spread far beyond both Cornwall and the Antiquarian circles of

London. Often publications coincide with an event or an anniversary, although

articles from the Cornish press are far more frequent and span the entire

period from her death.

How is Dolly Pentreath remembered and commemorated today? Within

the Cornish language community and language history scholarship, it is

generally accepted she does not represent the death of Cornish, but she

continues to be marketed as such in products aimed at tourists, and her image

is used on many items. What I found interesting from a cursory Google search

was an antique door knocker which mentions Pentreath’s age at her death as

being 102 and marketed at the witchcraft or wiccan market. I’m not sure what

the link there is supposed to be.

Of greater interest to my research is a porcelain figurine

from the Royal Cornwall Museum collection. [3] Pentreath is named on the front,

but on the back is painted the date 1753, fifteen years before Barrington

visited Mousehole. The museum’s catalogue only contains the provenance of the

item, nothing about its previous history, or if it can be traced to a

particular Staffordshire pottery. I have found reference to other examples

being sold at auction, again dated 1753, but have not found any further

information as to whether this is accurate. This raises many questions as to

how Pentreath was known of in Staffordshire at this time.

Kensa Broadhurst is a 3rd year PhD candidate at the Institute of Cornish Studies, University of Exeter. She is funded by the Cornwall Heritage Trust and the Q Fund. She is researching the status of the Cornish language between 1777-1904, that is, the period in which it is widely considered to have been extinct. A former modern languages teacher, Kensa is a fluent speaker of Cornish and a Bard of the Cornish Gorsedh. She teaches an undergraduate module in Cornish at the University of Exeter.

Notes

1. Paul Parish Registers, MOR/REG/16, Morrab Library, Penzance.

2. Dr Jago, English-Cornish Dictionary as it went through the press, also Original Letters about Dolly Pentreath, Courtney Library, Royal Cornwall Museum, Truro.

3. Figure of Dolly Pentreath, TRURI: 1944.111.162, Royal Cornwall Museum, Truro.

Comments

Post a Comment