‘Trade is the Life of the Nation’: Economics in the petitions of Elinor James (1681–1716)

Dr Rosalind Johnson, Visiting Research Fellow, University of Winchester, presented a paper on the petitions of seventeenth-century businesswoman Elinor James at the WESWWHN Annual Conference on Women and Money: A Historical Perspective in 2022. In this blog, she explores the content and motivation behind James’s appeals to monarchs, politicians and alderman.

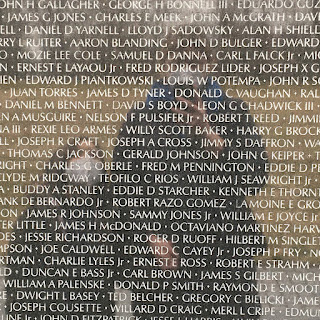

Elinor James (née Banckes, c.1645–1719), petitioner and printer, authored some ninety known printed papers during the period 1681–1716, addressed to six monarchs, both houses of parliament, and the Lord Mayor and aldermen of the City of London. Her petitions discussed matters concerning trade, religion, the monarchy, and other aspects of current politics, and her activities in promoting her causes ensured she was well-known to her contemporaries. Many of James’s petitions referenced finance, both in trade and in household economics, and her concern is evident in these for the economic situation of those whom she saw as affected by government policies.

Several of James’s petitions reference the printing trade. Her husband, Thomas James (d 1710), was a master printer, and James’s own knowledge of printing informed her petitions on the trade. As the mistress of a print shop, she would have been living in premises that were both a place of work and a domestic dwelling, and her petitions illustrate her understanding of the trade; she went on to run the print shop for several years after her husband’s death.

|

| Elinor James |

In 1695 the Licensing Act lapsed, and with it government control of the press, including restrictions on the numbers of master printers, journeymen and apprentices. James petitioned the House of Commons arguing against this deregulation of the trade, since she believed that without control of the press there would be a proliferation of printers, with no guarantee of sufficient work to support them. Although she mentioned the dangers of importing potentially treasonable books from abroad, her main concern was not the lapse of press censorship, but the threat to the printing trade of deregulation.

A further concern to the print trade was any imposition of taxes on paper, and in the period 1696-1702 James issued three petitions on this topic. The issue affected other trades as well; in January 1695 the Commons were petitioned by stationers on this matter, and in April 1699 no less than four petitions were sent in by affected trades.

James also petitioned on the dangers of government policy concerning the East India Company. As a joint-stock company it had many small investors, of whom her husband was one. Between c1695 and 1701 Elinor authored six known petitions that addressed, wholly or in a large part, East India Company (EIC) issues, and two further petitions that mentioned the EIC alongside other matters. In c1695 she petitioned in support of Sir Thomas Cooke, deputy-governor of the EIC, when he was accused of bribing MPs to influence their votes in support of the EIC’s trade monopoly. When a ‘new’ EIC was established alongside the ‘old’ EIC in 1698, she sought support for the rights of the original company’s shareholders. In one petition, addressed to the House of Lords, she urged the Lords not to, as she wrote, ‘undo Hundreds of Widdows and Fatherless, who have all their Substance in the East-India-Company’ and who would, Elinor warned, overwhelm any charities established for their relief.

Elinor did not explain the personal reasons for her support of Cooke, and later for the Company itself, but these became clear in a petition dated to 1698 or 1699. In this, she admitted that her husband Thomas was a shareholder in the East India Company. She denied that this was behind her petitioning, rather it was ‘the consideration of Thousands being undone’, a concern she had expressed in her earlier petition to the Lords.

In a later petition, probably of 1701, also to the House of Lords, Elinor petitioned against taxes on goods from the East Indies. Many of these goods were textiles, especially silk and cotton from India. Elinor claimed that taxes ‘make no advantage to the Weaver’, in other words, English weavers received no advantage from taxes and restrictions on imports. The weavers may have disagreed; four years previously, early in 1697, concerned at the rising tide of cotton imports from India, silk weavers from the Spitalfields area of London had walked to Parliament to support the passage of a bill prohibiting the import of Indian and Persian silks, and the weavers also marched on the East India Company’s headquarters.

When Elinor claimed, in 1701, that taxes and restrictions on East Indian textiles were of no advantage to English weavers, she was appealing in vain. In 1701 restrictions were placed on the imports of a wide range of cotton and silk goods, and custom duties raised on imported plain calicoes in 1701, and again in 1704 and 1708. As for the ‘old’ and ‘new’ East India Companies, the ‘old’ company, by buying shares in the ‘new’, quickly attained dominance over its erstwhile rival, and in 1708 – or 1709, depending on which source one reads – the two companies were merged.

James’s petitions have been collected as facsimiles with a scholarly introduction by Paula McDowell, but other than McDowell’s work, James remains little studied by scholars of women’s history. This may be because in her petitions James did not define herself by her gender; she invariably petitioned not as a woman, but as a concerned citizen. Yet as a woman who boldly petitioned those in power, she is a worthy subject for further study. Furthermore, her political and religious leanings were conservative, not radical, in spite of her repeated addresses to those in power. Is there is a tendency among historians to prefer the histories of radicals over traditionalists? And if this bias exists, should it be redressed?

Further reading: Paula McDowell (ed), The early modern Englishwoman, essential works: Elinor James (London: Ashgate, 2005).

Rosalind Johnson is a visiting research fellow in the School of History and Archaeology at the University of Winchester, where she was awarded her PhD in 2013. She has taught at the universities of Chichester and Winchester, and currently works as a contributing editor for the Wiltshire Victoria County History project. Her research usually focuses on 17th and 18th century Protestant nonconformity, on which she has published several journal articles and book chapters. The research into Elinor James is a new departure, and she is looking forward to undertaking further work on this topic, in particular contextualising Elinor James within the activities of female petitioning more generally.

Picture Credit:-

Eleanor James, by Unknown artist, oil on canvas, circa 1690, NPG 5592

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Comments

Post a Comment