Fashion and Politics in the US Women's Suffrage Movement

Claire

Delahaye delivered a presentation on the intersection of fashion and politics

in the US women’s suffrage movement of the early twentieth century at the

WESWWHN Annual Conference on Women and Fashion in Bath on 12 October 2024. This

paper argued that fashion provides a valuable lens for examining various

aspects of the US women’s suffrage movement, particularly through the

politicization of dress and the aestheticization of politics. It explored the

relationship between suffragists’ clothing choices and their political

practices, focusing on what they wore during public political activities.

Rather than serving merely as a symbol, suffragists’ attire functioned as a

tangible, practical tool – an essential element of their daily political

operations and campaigning efforts.

Indeed,

suffragists strategically selected clothing that was both functional and respectable,

recognizing that their success in outdoor activities depended on suitable attire.

Comfort, warmth, and freedom of movement were essential to the experiences of

field workers. As suffragists carried out their work in the streets, their

clothing and accessories needed to accommodate practical needs, providing space

to carry essential materials for their activities. Newspapers noted the

importance of pockets for suffragists, while bags, purses, and satchels became

crucial for storing items needed for political work. [1] In the 1910s, the National

American Woman Suffrage Association’s official newspaper The Woman’s Journal

coordinated an organized sale force and published articles and letters encouraging

women throughout the nation “to order the Journal’s trademark yellow and

black canvas “newsy bags” and take to the streets.” [2]

Sartorial

choices played a significant role for suffrage leaders, who urged women to wear

specific clothing to project an idealized vision of female citizenship,

effectively imposing dress requirements on marchers. [3] This authoritative

stance underscored how fashion functioned as a tool of collective discipline,

revealing complex power dynamics within the movement – a particularly along

lines of race and class. Prescriptive guidelines for parade attire often

excluded women with limited financial means, reinforcing class tensions among

suffragists. In response, some activists used their clothing as a form of

resistance, expressing their dissatisfaction with what they saw as an

infringement on their personal freedom by suffrage leaders.

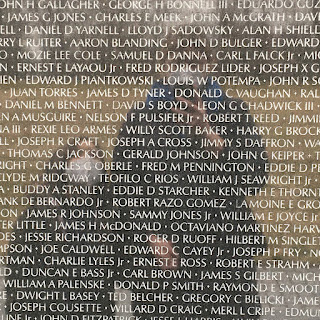

The

different accessories (hats, pennants) women were asked to wear for parades.

Moreover,

for some suffragists, clothing served as a subtle yet powerful site of

resistance. Pockets, in particular, symbolized both intimacy and political

defiance, providing women with a space they controlled. These small, personal

compartments held everyday items that could unexpectedly be repurposed as

political tools, reinforcing the intersection of fashion and activism. For

example, when suffrage leader Alice Paul arrived at the workhouse after being

arrested in 1917, she had a volume of Robert Browning in the pocket of her

coat. When prison matrons refused to open the windows, Paul hurled her book

through the glass, breaking a pane to let in fresh air. [4] This anecdote

highlights how clothing functioned as a form of concealment, enabling women to

discreetly carry everyday objects that could be transformed into tools for

direct political action.

When

Congress met for its last session on December 4, 1916, President Wilson

delivered a message that ignored the subject of women’s suffrage. Knowing this

in advance, the suffragists prepared a sensationalist action. They unrolled a

large banner during the president’s speech, asking for suffrage. Suffragist Mabel

Vernon had been given the difficult task of bringing the big banner of yellow

sateen inside. She pinned it to her skirt, under the enveloping cape she wore. [5]

When the National Woman’s Party picketed the White House in the summer of 1917, mobs started attacking them. Suffragists then carried their banners “inside their sweaters and hats, in sewing bags, or pinned them, folded in newspapers or magazines, under their skirts. One picket was followed by crowds who caught a gleam of yellow at the hem of her gown.” [6] In this instance, clothes were used to conceal banners, as the “pickets distributed the banners in different parts of their clothes,” showing that pieces of clothing play a specific role in activism. In the same manner, when they started “Watchfires of Freedom” on the White House pavement, they hid “logs under coats and capes” to hide them from the policemen. [7]

These

examples show that some suffragists politicized their clothing in surprising

and cunning ways. They even reversed the stigmas attached to wearing prison

clothes and exploited it to shock US public opinion. Indeed, after National

Woman’s Party members were arrested and imprisoned, they replicated the prison

clothes to tour the country aboard the “prison special.” [8]

The relationship between suffragists’ clothing practices and political strategies underscores both the politics of material culture and the material culture of politics. Suffragists viewed dress as a crucial tool in their activism, yet it also exposed ideological divisions and class tensions. The recommendations and requirements set by suffrage organizations highlighted the friction between clothing as a means of personal self-expression, a marker of collective political identity, and an instrument of organizational discipline.

Notes

[1] “Plenty of Pockets in Suffragette Suit,” New York Times, October 10, 1910, p. 5; “Dame Fashion Suffragist,” New-York Tribune, March 6, 1913, p. 7.

[2] Margaret Finnegan, Selling Suffrage : Consumer Culture & Votes for Women, New York, Columbia University Press, 1999, p. 148.

[3] “Mrs. Foster Attends Suffrage Parade,” Maryland Suffrage News, November 16, 1912, p. 132.

[4] Inez Irwin, The Story of the Woman’s Party, New York, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1921, p. 285.

[5] Irwin, p. 180-183.

[6] Irwin, p. 233.

[7] Irwin, p. 470.

[8] Katherine

Feo Kelly, “Performing Prison: Dress, Modernity, and the Radical Suffrage

Body,” Fashion Theory no. 15, vol. 3 (2011): 299–321.

doi:10.2752/175174111X13028583328801.

Picture

Credits:-

Lucy Branham in prison dress - Harris &

Ewing, 1919, Library of Congress, No known restrictions on publication. (There

are no known restrictions on photographs by Harris & Ewing.)

The different accessories women (hats, pennants) women were asked to wear for parades - Members of the Woman Suffrage Association of Mongomery and Dayton County, 27 August 1912, public domain in the country of origin (US).

Comments

Post a Comment