Spaghetti, Sardines and Semolina: Changes in the Food Supply on the Home Front 1914 to 1918

Helen George explains the ways in which rationing influenced how people shopped and what they ate during the First World War in this fascinating post based on a talk she gave at the WESWWHN Conference on Historical Perspectives on Women and Food in 2025.

Ration cards, powdered eggs, long queues for food: they usually conjure up visions of the Second World War Home Front. However, through my research into home life during the First World War I have found that they were very much part of daily toil a generation earlier. Between 1914 and 1918 submarine warfare decimated merchant shipping, leaving import-dependent Britain dangerously short of food. What of the young wives and mothers struggling to feed their families and manage household budgets as their menfolk joined the Armed Services? They had to change their shopping practices, manage their homes with fewer or no domestic servants, cope with acute food shortages, encourage their families to try new foods and, during the last year of the war, become accustomed to compulsory food rationing.

I chose to focus my research on the Hertfordshire town of Watford. During the 1890s and 1900s rows of new terraced houses had sprung up in a speculative building boom. Young people from the surrounding countryside had flocked to the town to take up plentiful job opportunities in brewing, chocolate making, printing, building and railway work. High birth rates, and a comparatively low infant mortality rate, meant that by 1914 Watford’s population was dominated by young families. Editions of the Watford Observer, marriage and baptism records, council meeting agendas and minutes, and annual medical reports have provided a compelling picture of daily life during the war.

During 1914 and 1915 Watford’s young men volunteered for the Armed Forces in large numbers, leaving their peacetime jobs vacant. As a result, their wives could supplement army separation allowance incomes by taking up employment in shops, offices and munitions factories. Council-sponsored nurseries and creches would assist them in doing this. They could then spend their extra incomes on “new foods” which had not previously been popular but were in plentiful supply. In place of the meat, potatoes, white bread and tea of the pre-war years, Watford’s Local Food Control Committee urged residents to adopt a diet of macaroni, spaghetti, maize flakes, semolina, oatcakes and sardines. Packet soups, powdered eggs and pre-made blancmanges emerged from the town’s Delectaland food factory. Top quality coffee, imported to keep Brazil and Columbia on the allied side, was widely available and marketed rigorously by local grocers. When food rationing was introduced in New Year 1918, guaranteeing fair shares of meat, butter and sugar, a Watford household could be eating a more varied diet than before the war.

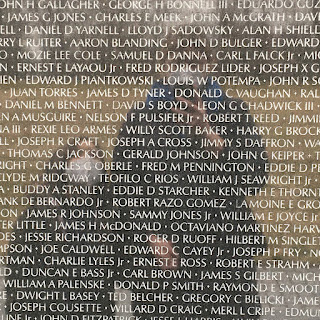

Ration book issued to a demobilised soldier in Watford, 1918.

What was the impact upon the health of mothers and their children in Watford? The town’s annual medical reports between 1914 and 1919 shows that infant mortality (measured by the number of deaths per 1,000 children aged under 12 months), premature births, and death in newborns due to Congenital Debility and Malformation all declined during the war. These changes might partly stem from successful local Mothercraft movement campaigns and the work of Watford Council’s Maternity and Infant Welfare Committee; during the war its members introduced a range of measures to promote the health and wellbeing among both mothers and babies. However, improved nutrition may also have contributed to these splendid improvements in health.

The editions of the Watford Observer in the 1920s show no sign that the “new” foods were consumed widely during the post-war years. Adverts for meat, bread, butter, margarine and tea began to adorn the pages of the local newspaper as the new decade began. Those popular pre-war foods were again available in abundance. Perhaps returning servicemen had demanded a return to the diets they had enjoyed before going off to war? Nonetheless, the ladies of First World War Watford certainly worked hard to ensure that their families were well-fed, and deserve enormous credit for the battles they fought and won on the Home Front. Undoubtedly, these ladies of the town were able to dispense invaluable advice on wartime housekeeping to their daughters a generation later.

Helen George studied for a B.A. Honours degree in history at the University of Exeter and a Masters Degree in Social History at the University of Warwick. She is a specialist in twentieth century social history. She carries out research into aspects of life and Hertfordshire and Warwickshire. In 2023 she was one of five individual winners of the National Archives’ and BALH’s 20sStreets competition.

Picture Credit

Demobilization ration book: soldier, sailor, or airman, 1918, Wellcome Collection, Public Domain.

Comments

Post a Comment